Voter Satisfaction Efficiency, or VSE, is a measure of the quality of a election method. A VSE of 100% would mean an impossibly perfect method; 0% or lower would mean that the society would be better off picking a winner at random.

To calculate VSE, you simulate thousands of elections, using voters who cluster on issues in a realistic way. Since the voters are simulated, you can know exactly how satisfied they would be by each candidate; that is, how close the candidate is on the issues they care about.

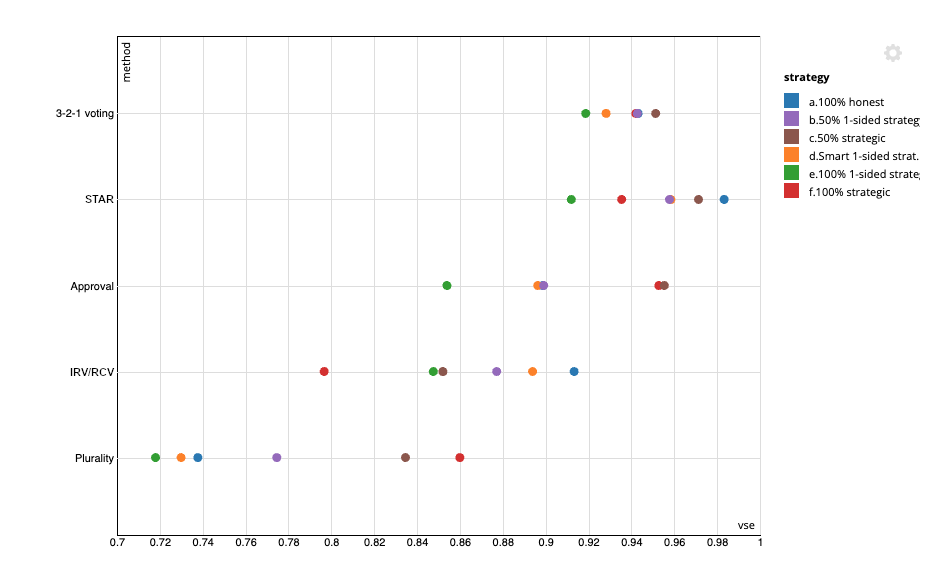

I’ve run VSE simulations for a number of methods. Here’s a chart with only the best and most well-known methods:

-

Plurality voting, also known as choose-one plurality or first past the post: This is the most common election method in the English-speaking world. It’s also in most situations the worst out of all the methods I’ve tested, with a VSE of only around 75%. It often gets “spoiled” results, where a weaker candidate wins due to vote-splitting; it encourages strategy; and it leads to uncompetitive politics, dominated by big parties (and their big donors) who get their votes as much through fear as through hope.

-

Approval voting is a voting method where you can “approve” (support) as many candidates as you want, and the candidate approved by the most voters wins. Its VSE is around 89-95% for most levels of voter strategy. That’s not the best of the methods I tested, but it certainly is the best “bang for the buck”; a simple reform, with basically no downsides, which improves outcomes hugely.

-

3-2-1 voting is a voting method where voters give each candidate one of 3 ratings — good, acceptable, or bad — and you find the winner in 3 steps. First, the 3 semifinalists are the candidates rated “good” the most; second, the 2 finalists are the semifinalists rated “bad” the least; and third, the winner is the finalist who’s rated higher on more ballots (ie, the winner of a virtual runoff). This method’s VSE runs from 92-95%, even with strategic voters. Also, because it’s one of the methods which best avoids giving an unfair advantage to those strategic voters, and because its simple ballot format is approachable for all voters, it encourages honest (non-strategic) voting. In my opinion, this is the best single-winner election method for large-scale political elections with diverse voters.

-

STAR Voting (Score then Automatic Runoff), also with different possible score levels. This is like score voting (explained below), except that you choose the top 2 candidates based on scores, and then find the one of them who’s rated higher on more ballots (ie, the winner of a virtual runoff). With enough possible score levels, this has a VSE of 91% all the way up to 98% — better than even 3-2-1 voting. The only reasons I chose to highlight 3-2-1 voting above this method is that 3-2-1 has a simpler ballot and resists strategy slightly better. But STAR is undeniably a top-shelf election method, and arguably the best out of all the ones I tested.

Some other methods I’ve tested, but (aside from IRV/RCV) left out of the figure above, include:

-

Score voting with a varied number of possible score levels. This is a method where voters give from 0 to some maximum number of points to each candidate, and the highest average score wins. This method is great when voters all agree on the goals, and merely need to find a candidate who will best implement those goals. But in more contentious situations, such as most political elections and those I tested, it’s vulnerable to voting strategy, which can take its VSE from 96% down to 84%.

-

Condorcet methods such as Schulze and Ranked Pairs. In these methods, voters rank candidates in preference order, and any candidate who can beat all the others pairwise is the winner. These methods also topped out at 98% VSE, though they seem slightly more vulnerable to strategy than STAR; Ranked Pairs, the best Condorcet method I tested, can have a VSE as low as 86% under strategy. However, the complexity of vote-counting and of presenting results in these methods makes them, I feel, more theoretical than practical.

-

Instant Runoff/Ranked Choice Voting (IRV/RCV). In this method, voters rank candidates in preference order and the favorites are tallied. Then, there’s a process of eliminating the last-place candidate and re-tallying their votes for the voters’ next preference (if any), until one candidate tallies more than half of the remaining votes. This method’s VSE runs from 92% with honest voters down to 79% with all strategic voters. That’s better than plurality, but worse than all the other methods above. Still, this method is notable, because it has the strongest track record of any of these methods except plurality; it’s been used in thousands of political elections in multiple countries and jurisdictions.

-

Median-based (Bucklin) methods such as Majority Judgment or Majority Approval Voting. These methods are the only ones whose practical strategy resistance is significantly better than 3-2-1 voting; but unfortunately, their VSE tops out at 92%.

-

The Borda count, in which voters rank candidates in preference order, candidates get points based on what order they’re given, and the highest points wins. As Borda (this method’s 18th-century inventor) himself said, this is a good election method “for honest men”; unfortunately, under strategy, it can actually have a VSE below 0%, electing a candidate precisely because the voters expect them to be the biggest loser.

Other assumptions about approval voting:

- The issue is that in approval voting, it’s not entirely clear what constitutes an “honest vote”; how many candidates should a voter approve? This has led some people to criticize the method, suggesting that it leads to too many “bullet votes” for just one candidate. However, when I tested the method with realistic clusters of voters and issues, I found that including up to 70% of bullet voters actually improved the outcome by a tiny amount, making it slightly more robust against strategy (whether or not the strategic voters bullet voted). Thus, I find this criticism to be without merit.

If you want to see a figure which includes all of the above methods, see here.